Manston’s role in Operation Market Garden, 17th September 1944

Main Image: An Armstrong Whitworth Albemarle of either No. 296 or 297 Squadron RAF, taking off from Brize Norton, Oxfordshire, with an Airspeed Horsa Mark I in tow. © IWM (CH 12962)

A slowing advance and a plan

By September 1944, Paris and Brussels had been liberated through weeks of heavy and costly fighting through the Normandy fields and hedgerows, after the triumph of the D-Day landings in June. Victory for the allies seemed close, but as the push neared Germany’s borders, their resistance stiffened and the broad front of the Allies became difficult to supply from the few ports that they controlled and the limited remaining rail network. The approaches to the port of Antwerp still remained to be cleared and recently captured Ostend and Dieppe had limited cargo capacity. Only Cherbourg, some 450 miles from British positions and 400 miles from US forces in eastern France, was capable of handling significant level of supplies.

The commander of the British forces in Europe, General Bernard Montgomery, conceived the plan for a powerful, narrow thrust deep into German lines, which could have ended the war by Christmas 1944, but also stop the attacks on London by the V2 rockets in the area. It was known that a general advance was out of the question until Antwerp could be cleared and that could allow the German’s valuable time to recover. Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander, however favoured a general move forward.

Operation “Market Garden”

Operation “Market Garden” was one of the boldest plans of World War II. The Operation “Market” part would consist of nearly 40,000 British, American and Polish airborne troops flown behind enemy lines to capture the eight bridges that spanned the network of canals and rivers on the Dutch/German border. Dropping by parachute and in gliders, these divisions would land near the Dutch towns of Eindhoven, Nijmegen and Arnhem. Operation “Garden” would be a simultaneous push up a narrow road by British tanks and infantry from the Allied front line that lead to these key bridges. They would relieve the airborne troops and cross the intact bridges.

Fifteen operations for airborne troops were planned and then cancelled, with 1st Airborne, unlike its sister division, 6th Airborne, not even required to protect the British flank after D-Day. After Operation “Comet”, the last of the cancelled operations, conceived on the 2nd September and scheduled for the 8th September 1944 was delayed and then cancelled. The plans including British airborne and the Polish brigade without American support were adapted to form Operation “Market Garden”, but retained the same objectives. “Comet” was cancelled seemingly on the protests by the Polish Commander, Major-General Stansilaw Sosabowski and others who thought it would be a suicide mission.

“Market” would be the largest airborne operation in history, delivering over 34,600 men of the 101st, 82nd and 1st Airborne Divisions and the Polish Brigade. 14,589 troops were landed by glider and 20,011 by parachute. Gliders also brought in 1,736 vehicles and 263 artillery pieces. 3,342 tons of ammunition and other supplies were brought by glider and parachute drop.

The combined force had 1,438 C-47/Dakota transports (1,274 USAAF and 164 RAF) and 321 converted RAF bombers. The Allied glider force had been rebuilt after Normandy until by 16 September it numbered 2,160 CG-4A Waco gliders, 916 Airspeed Horsas (812 RAF and 104 US Army) and 64 General Aircraft Hamilcars. The U.S. had only 2,060 glider pilots available, so that none of its gliders would have a co-pilot but would instead carry an extra passenger.

Problems even before it began

Although there was less objections to the much larger venture of “Market Garden”, with the original “Comet” force being supplemented by two American airborne divisions and an increase in supplies, Sosabowski although happier, still had grave concerns. He expected there would be a higher enemy presence in the area than British intelligence suggested. Although eventually found to be correct, SS Panzer Divisions were only moved to the region by chance. He, probably amongst others, were aghast that the drop zones would be some miles from the bridges and the entire lift operation would take place over a period of three days because of the lack of aircraft and the decision to take a headquarters to the battle. Even at the outset, it was a plan where so much could go wrong.

Troops being readied were the 82nd and 101st US Airborne Divisions, 1st and 6th British Airborne Division, the Polish Independent Parachute Brigade Group and an SAS unit.

“Market Garden” was set to commence on Sunday 17th September 1944.

Lieutenant-General Browning, deputy to Lieutenant-General Brereton who was in overall charge of the British and American airborne units and the transport units they required, and a veteran of World War I, was anxious to command troops in battle before the war ended. Normal practice was for airborne divisions were dropped independently and came under command of the relevant ground forces corps headquarters when a link-up was achieved, just as it had on D-Day. However Browning secured agreement that an airborne corps headquarters would take part in the operation, even where the three divisional drops would be scattered and the corps commander of the American forces was battle experienced at Normandy. Browning and his staff would fly in by glider and land in the middle of the three drop areas, near Nijmegen. This decision would not only come to scrutiny later because of the communication issues in the battle, but also the glider lift of the headquarters would require 38 tug aircraft from the limited force available.

The British 1st Airborne Division with the Polish Brigade were assigned to capture the main road bridge, a railway bridge and a pontoon over the Lower Rhine at Arnhem. It was hoped that they could be reached in three days or less by the Second British Army, starting 64 miles away at Neerpelt.

Preparations at Manston

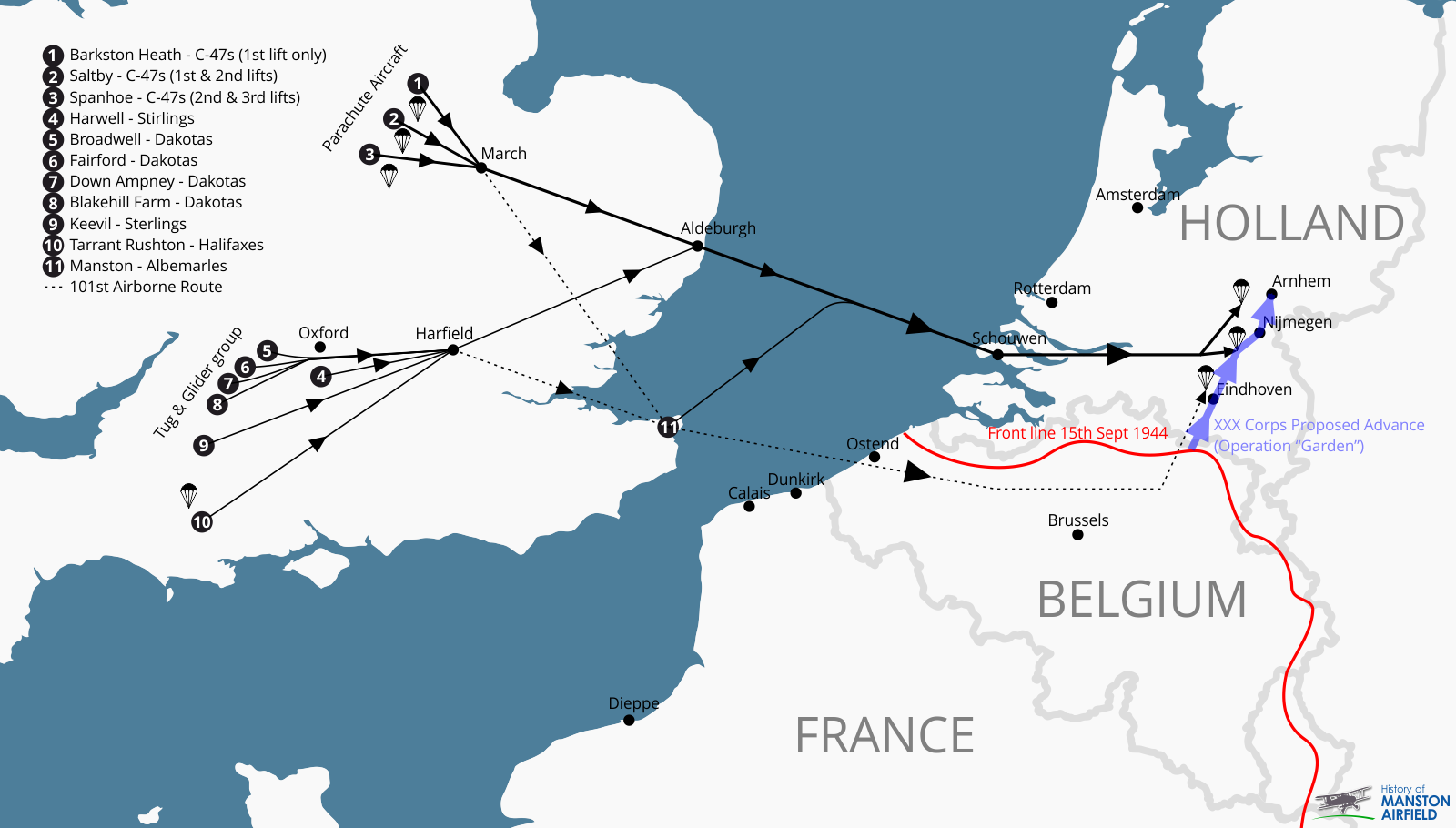

Parachute aircraft would consist of US C-47 Douglas Dakotas from Barkston Heath, Saltby and Spanhoe. The glider group would be towed by Short Stirlings from Harwell and Keevil, Halifaxes from Tarrant Rushton and Dakotas from Broadwell, Fairford, Down Ampney and Blakehill Farm. Manston was to be used for the Armstrong Whitworth Albemarle of 296 and 297 Squadrons and gliders they were to tow, as their twin-engined aircraft could not reach Arnhem with a fully loaded glider from their home airfield at Brize Norton.

On 5th September 1944, 37 Horsa gliders from Brize Norton complete with airborne personnel arrived at Manston in the build-up to “Comet”. Initially set to leave at 0800 hrs, their move was postponed until 1100 hrs then to 1500 hrs. At 1500 hrs, the lift from Brize Norton commenced in very squally weather. D Company HQ glider (Major Phillip) failed to take off because of a defect in the tail of the glider. Another glider of B Company, with Lieutenants Norwood and MacDonald, crashed on take off, although no serious injuries were sustained. Both gliders were re-scheduled to take off the next day.

The next day, 6th September, gliders and tugs full of men were ferried to Manston, ending with thousands of airborne troops at the airfield and catering and accommodation severely strained. The remaining gliders from the previous day, left Brize Norton at 0900 hrs. 13 Platoon of the 2nd South Staffordshire’s glider returned to Brize Norton after crash landing just outside of Oxford, again without casualties. Arrangements were made for this platoon to be transferred to Manston by road, with a replacement glider flown down in ballast. Fifty-six aircraft from 296 and 297 Squadrons, towing their Horsa gliders eventually flew in to Manston.

On 7th September, heavy rain the night before forced troops to evacuate their tents for dry accommodation. Rain continued until well after midday and created difficulties being able to marshal gliders and tugs. Later that day, the Commanding Officer and Intelligence Officer from the South Staffordshire arrived by road at 1615 hrs and started the briefings for “Comet” at 1700 hrs, only for it to be postponed at 2230 hrs for 24 hours.

On 8th September, again “Comet” was postponed for tactical reasons.

On 9th September, crews and troops now used to the postponements expected another, which indeed postponed for a further 48 hours. Six gliders and crews went up in the afternoon to test a new take-off system which worked well.

On 10th September, after a church parade at 1100 hrs, word was received in late afternoon that “Comet” had been cancelled. At 1730 hrs, the South Staffordshire troops were allowed out of the camp, although few took up the offer down to having plenty of foreign currency, presumably ready for the operation, but no English money.

On 11th September, the South Staffordshire’s Commanding Officer and Intelligence Officer returned to Brize Norton. At Manston, a field cashier arrived in the afternoon to exchange the foreign currency leading to a larger influx of airborne troops into the local towns.

From the 12th to the 16th September, personnel of the South Staffordshire were either on leave or carrying out PT and games. The Commanding Officer and Information Officer returned on the 16th by plane from Brize Norton.

Despite Manston’s long runway and large dispersal area, the airfield was still crowded. There were 12 RAF and Fleet Air Arm squadrons stationed there, mostly fighter squadrons operating against the V-1 flying bombs, or standing by to either escort the air armada to Holland or to carry out supporting operations on German installations such as flak sites. Such was the strain upon the resources of the airfield that on 8th September, an Albermarle and a Horsa was flown back to Brize Norton to return with a load of WAAF waitress reinforcements.

Warnings

On 12th September, Major-General Urquhart briefed the brigadiers, brigade majors, commanders and staff officers. When the plan was relayed down to the 1st Battalion officers, they objected without exception to the dropping zone because of its distance to the bridges. A request was sent to higher command to drop closer to the objective, but it was refused.

On 15th September 1944, Major Brian Urquhart attempted to point out the danger of a build-up of German armour in and around Arnhem. Reports included information that two SS Panzer divisions were believed to be in the area. None of the reports were precise so Major Urquhart ordered photo reconnaissance by a Spitfire, which provided prints of modern Mark III and Mark IV tanks close to Arnhem. He took all the new evidence to General Browning who rejected it and sent Major Urquhart on sick leave. All the initial planning was convinced that there would be little resistance from the Germans, but perhaps General Browning just saw it as being too late. No warnings of the Panzers was sent to the commanders before they took off.

Operations from Manston

On 17th September 1944, at 1030 hrs, the first lift started for Holland. At Manston, 296 and 297 squadrons made the largest contribution in aircraft numbers, dispatching 28 Albermarles each. No other RAF squadron managed more than 25. 296 Squadron towed 26 Horsas and 2 Wacos to Arnhem without loss. 297 Squadron towed twenty-five Horsas to both of the landing zones at Arnhem, with a further three to Nijmegen with Waco gliders carrying sections of 1st British Airborne Corps HQ. The Manston glider loads were anti-tank and light artillery, part of the 2nd South Staffords infantry and four Waco gliders carried the American signalling teams brought forward from the second lift towed by four Albemarles that flew in the morning from a reserve unit. Five reserves actually flew in but were told they would be in the way so were told to return, with only one taking up the offer before the other four were found to be required.

For the total operations, there were some casualties however, Of the 320 gliders that had taken off from England, 283 landed on or close to the landing zones, including the four Wacos with US radio parties not due until the next day. Eleven men of the British side of “Market”, mostly glider pilots were killed or die as a result of landing incidents. One Para died when his parachute failed to open properly, one from a firearm incident and four from enemy action. US air units carrying the 82nd and 101st were not as fortunate, with no less that 35 C47-s being lost. Amongst those were 27 from the 53rd Troop Carrier Wing caught by flak mostly after dropping their parachutists near Eindhoven.

The video above (© IWM (AMY 130)), from the Imperial War Museum collection shows various sequences of the initial airlift. If you look closely for the twin-engined Albemarles with their easily identifiable tails, you should be able to spot several sequences at Manston, including a sweep over the runway. Edit (4/10/2016): The version posted above at the time of the post has now been withdrawn, but you can watch a version with a less intrusive watermark, if your device supports flash, here: http://film.iwmcollections.org.uk/record/index/18174

The Manston Tempest Wing (80, 274 and 501 Squadrons), led by Wing Commander Wray, successfully attacked flak positions in the Dutch Islands over which the flights to Arnhem would travel. By midday, damaged aircraft started to return. The Tempest Wing and the West Hampnett Wing that had been forward deployed to Manston flew again in the afternoon on armed reconnaissance and to protect the returning aircraft. The West Hampnett Wing of Spitfires took off at 12:50hrs to provide close fighter cover escort and to neutralise the flak for a force of sixty-seven Sterlings. Led by Wing Commander John ‘Johnny’ Milne Checketts DSO, DFC, seven Spitfire Mk.IXFs of 303 (Polish) Squadron reached Arnhem at 14:10hrs. Flying Officer Witold Aleksander Herbst was hit by flak and he baled out over northern France. Witold completed a total of 141 combat missions in a Spitfire and survived being shot down several times.

On 18th September, the second lift, held up for nearly five hours because of fog in England, saw 296 Squadron bring in twenty-four Horsas. Again, no losses were sustained which was fortunate, as the Luftwaffe were waiting for the lift at 10:00hrs, after the plans for “Market Garden” had been found in an abandoned glider, which should never have left England. 297 Squadron towed twenty-one Horsas to Arnhem, but two did not arrive. One glider become disconnected from its Albermarle five minutes after take off and crash landed. The glider pilot remarked that the same thing had happened to him on D-Day. Ten of the Horsas carried the first element of the Polish brigade – five anti-tank guns and a small Brigade HQ advance party, twenty-six men in total. Again, the Tempest Wing carried out anti-flak patrols and forty-two Albermarles returned to Manston.

On 19th September, the third wave saw 296 Squadron with one aircraft taking one of the Horsas that failed to arrive on the previous day. The West Hampnett Wing was involved in providing escort to gliders and tugs operating in the Rhine Delta, but because of bad weather the escort was abandoned and the Wing returned to Manston to spend the night.

Also on the 19th, a Walrus brought back four survivors of a glider crew from an air sea rescue patrol over the Albemarle’s route.

With the Albemarle unsuitable for resupply flights that took over now the airlift was complete, 296 and 297 Squadrons played no further part in “Market Garden”.

For several days, the weather deteriorated and flying was curtailed, apart from the night of the 23rd when 504 Squadron escorted Dakotas and Stirlings that were dropping supplies to the encircled forces at Arnhem.

On the 22nd September, three Dakotas from 233 Sqn took 54 Spitfire drop tanks to B56 (Brussels/Evere) as part of the sixth lift. On the 23rd September two Dakotas took petrol tanks to B56 as part of the seventh lift.

The Battle on the Ground

The assault by XXX Corps as part of Operation “Market” designed to follow through all the way to Arnhem to support the air troops, suffered from unexpected German resistance. Although the bridge at Nijmegen was eventually taken on the 26th September, the attack was costly for the American troops. Nothing then stood in the way to get to Arnhem, but by that time it was too late. German tanks had been moved into Arnhem and were demolishing the houses in which the British troops were fighting at the North end of the bridge and the were desperately short of suppliers and ammunition. German artillery controlled the river. Even the attempt by General Sosabowski’s Polish 1st Airborne Brigade on September 22nd to rescue the remaining British forces failed when they met strong resistance from German defence. On 25th September, the withdrawal of the whole 1st British Airborne was ordered. On the 27th, the remaining Poles surrendered to the Germans.

It can be argued that the Airborne Forces at Arnhem did not lose the battle, they were ordered to hold for two or possibly three days, they held out for eight days. They had rations for 48 hours. Some 6,400 of the 10,000 British paratroops who landed at Arnhem were taken prisoner, a further 1,100 had been killed. British casualties were higher than they suffered on D-Day.

Operation Market Garden had failed to reach its objectives. It would be another four months before the Allies crossed the Rhine again and captured the German industrial heartland. The war dragged on, costing the lives of many thousands of civilians and servicemen. Arnhem was finally and officially liberated on 14th April 1945 by Canadian troops. However it wasn’t a total failure as the corridor served as a route for further assaults on the Germans.

Statistics

First Allied Airborne Army had undertaken 4,852 troop-carrying aircraft sorties of which 1,293 had delivered paratroopers, 2,277 had delivered gliders and 1,282 resupply. 164 aircraft and 132 gliders had been lost with USAAF IX Troop Carrier Command suffering 454 casualties, RAF 38 and 46 Groups another 294 casualties. 39,620 troops had been delivered by air (21,074 by parachute and 18,546 by glider) as had 4,595 tons of stores. Only 7.4% of stores intended for 1st Airborne had reached it. Another 6,172 aircraft sorties were flown in support of Market Garden for the loss of 125 aircraft, against 160 enemy aircraft destroyed.

Whilst figures differ, one historian suggests that 11,920 troops of the 1st British Airborne Division and Polish 1st Independent Parachute Brigade had landed at Arnhem. This number also includes crews of the Gliders who, once landed would take part in the battle. Some 3,910 were evacuated safely (1,892 from 1st Airborne, 532 from the Glider Pilot Regiment, 1,486 Poles and 75 from the Dorset Regiment) and some 240 later with the help of the Dutch resistance.

The Germans claimed to have taken 6,450 men prisoner.

The 1st British Airborne fatal casualties stood at 1,174, glider pilots 219 and Polish at 92.

US 82nd Airborne casualty figures are reported as 1,432. US 101st Airborne reported as 2,118.

As part of Operation “Garden” XXX Corps suffered 1,480 casualties and VIII and XII corps 3,847 between them.

German forces suffered 3300 casualties (admitted by FM Model) although other estimates put the figure as high as 8000.

Units connected to operations from Manston

Divisional HQ and Defence Platoon Based at Fulbeck Hall.

Flew in seven C-47’s from Barkston Heath and Saltby and 29 Horsas from Fairford, Down Ampney and Manston. Went in: 142 men; died: 14; evacuated: 70; captured:58

1st Airlanding Anti-Tank Battery, Royal Artillery

Based at Heckington and Helpringham, with newly formed 17-pounder P Troop at Tarrant Rushton. Flew in 30 Horsas from Manston (mostly) and Blakehill Farm, 17-pounder troops in eight Hamilcars from Tarrant Rushton. Went in: 191 men; died: 24; evacuated: 52; captured:115

2nd Battalion South Staffordshire Regiment

Based at Woodhall Spa. Flew in over two days in 62 Horsas from Manston and Broadwell and a Hamilcar from Tarrant Rushton. Went in: 767 men; died: 85; evacuated: 124; captured: 558.

1st Airlanding Light Regiment, Royal Artillery

Based at Boston. The regiment (less No.2 Battery) flew in 57 Horsas from Fairford, Blakehill Farm, Down Ampney, Manston and Keevil on first lift; No. 2 Battery and others flew in 33 Horsas from Manston on second lift. Went in: 372 men; died: 36;evacuated: 136; missing: 200.

The Glider Pilot Regiment No. I WING (HQ Harwell)

A Squadron at Harwell, B Squadron normally at Brize Norton but flying to Arnhem from Manston, D Squadron at Keevil and G Squadron at Fairford.

US Air Support Signals Teams

Two teams, each of five Americans from the 306th Fighter Control Squadron with two British jeep drivers, flew in four Waco gliders from Manston. No fatal casualties; numbers evacuated and missing not known.

Statistics from here: http://www.marketgarden.com/2010/UK/statistics/statis1.html

Main Image: Shows an Armstrong Whitworth Albemarle of either No. 296 or 297 Squadron RAF, taking off its base at Brize Norton, Oxfordshire, with an Airspeed Horsa Mark I in tow. © IWM (CH 12962)

Further Reading

The Pegasus Archive: http://www.pegasusarchive.org/

“Arnhem 1944: The Airborne Battle”, by Martin Middlebrook, Penguin, ISBN 978-0-14-014342-3.

“The History of RAF Manston” by Flt Lt Rocky Steadman, ISBN 978-0951129807.

“A Fighter Command Station at War: A Photographic Record of RAF Westhampnett from the Battle of Britain to D-Day and Beyond”, by Mark Hillier, Frontline Books, ISBN 978-1473844681.

Flying Officer Witold Aleksander Herbst: http://www.bluehorizonfilms.net/index.html

Operation Market Garden (60th Anniversary report): https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/30056/ww2_market_garden.pdf

Disclaimer

Many of the figures based in this article are quoted differently in the various recognised sources. We have therefore based on figures we believe correct, but will amend if new certifiable information can be obtained. Other details may also be corrected as any issues are found.